The Caste System of Honey Bees

The 3 accepted honey bee castes explained. Wait… are there really only 2?!

If you go to google and type in “How many castes do honey bees have?” you will be met with an assumptious number: three. The search engine has chosen a side, albeit a very controversial side, and it does not show any signs of changing alliances in the near future. Just like the search engine, beekeepers are met with the same conundrum–how many castes do honey bees really have?

There are so many definitions of the word caste that they should be divided, respectively, and given new words to go along with. In biology, an accepted definition for caste is: “ a subset of individuals within a society of social animals that is specialized in the function it performs and distinguished by anatomical differences from other subsets.” If definitions don’t work for you, the key takeaway is this: individuals working together towards a common goal have designated roles, and it is often the case that each “type” of individual has evolutionarily evolved certain traits (both visible and not to an onlooker) to better assist in completing assigned roles. Entomologically, a caste is simply made up of a group of anatomically and behaviorally similar individuals within an insect society. The tricky part of the word caste is that it is attempting to combine both form and function, which is where the controversy takes root.

To begin an discussion that partially disputes the “all knowing” Google search engine, it is important to differentiate between sex and caste. In biology, the definition (last one, I promise!) of sex is: “a set of biological attributes and their functions in animals primarily associated with specific features including chromosomes, reproductive anatomy, and gene expression.” Again, form and function are intertwined in this definition, which reinforces the interconnected nature of these two biological descriptor words.

There are two sides to using the definition of sex in the debate on the honey bee caste system. While “the sex of the individual also plays a role in its designation as a caste, because castes occur within a sex,” separate sexes do not always necessitate assigning another caste within a species. This argues that sex needs to be taken into account when dividing the honey bee society into castes, namely that you can only assign castes if there are two roles played within one sex. On the other side, it can be argued that the sex of the individual does not play a role in its designation as a caste because castes can occur between the sexes. This asserts that sex does not need to be taken into account when dividing the honey bee society into castes, or that castes can only be assigned if there are one or more roles within a sex.

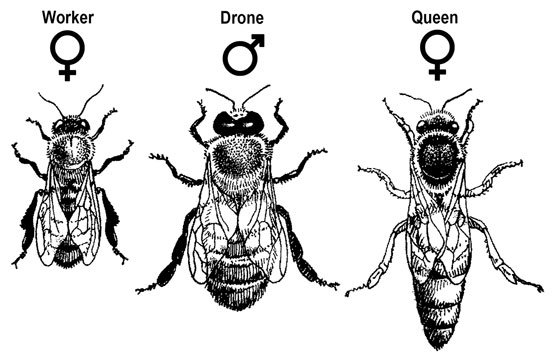

There are two honey bee sexes: male and female. The females all have 32 chromosomes, the males all have 16 chromosomes. The females all have ovaries, the males all have testes. The females all express genes that designate their role as caretaker of the hive, the males all express genes that designate their role as procreator.

Within the female sex, there are two caste divisions. Despite the controversy of the caste debate, this is pretty much agreed upon among beekeepers (and even Google)! There are two functions that female bees perform, and therefore they exist in two forms commonly referred to as “workers” and “queens.” Both worker bees and queens assume the role of caretaker, but they carry out this function using exclusive methods, which makes their separation into two castes necessary.

These two functions are dictated at conception when a queen bee lays an egg in either a “worker cell” or in a “queen cell.” If an egg lands in a queen cell, then the worker bees know to feed it royal jelly (a protein-rich secretion produced by worker bees, similar concept to breast milk in humans) throughout her development and entire life. If an egg lands in a worker cell, this larva will only receive royal jelly for the first three days after it has hatched from the egg (and subsequently is fed “bee bread,” which is fermented pollen and bee saliva!). Whether it is the royal jelly consumption or the lack of bee bread that causes the queen to be capable of sexual reproduction and grow physically bigger than the worker bees is still up for debate. Worker bees still do have ovaries, but they are only capable of laying unfertilized eggs via parthenogenesis asexual reproduction (which, in a complicated fashion means they can only lay drone-producing eggs) when the queen of the hive is struggling.

The second caretaking function of female bees is carried out by worker bees. Worker bees are dutifully named for all the various tasks they complete: they clean the hive, remove dead bees from the hive, they “nurse" the growing larvae, they guard the hive from intruders, and, most importantly, they forage for nectar and pollen. It is important to note that all of these roles are completed (in step) by every single worker bee. But then why do each of these roles not get assigned a separate caste? Because their form does not change over time to match the desired functional changes, rather the one physiological worker bee body completes all of these tasks. The queen never carries out any of these caretaking functions, but she is involved in communicating and organizing the occurrence of the duties. While worker bees do communicate (via bee dances, make sure to watch a video, it’s pretty cute!), they are not in direct control as the queen is (via complicated pheromones), but act more as a democratic body that works collectively towards the same goal: hive success!

Within the male sex, there are either zero caste divisions or one caste division. This is where the controversial third caste appears! All males perform the same function, and therefore exist in one form commonly referred to as “drones.” Their sole purpose is to mate with the queen. That’s it, nothing else! Drones only live maximally for eight weeks, and if one successfully mates with the queen they usually die in the process.

For all those unlucky drones who do not pass on their genetic material in a mating event, the end of summer entails being pushed out of the hive to succumb to the cold weather and starving conditions. This chain of events is evidence of the drones’ one sole purpose and proves that there is not a division of labor within the male sex. If they provided some other role to the hive, why would they be killed at a time when more bodies could create more warmth?

There are many supporters (including Google) of the three caste system—as it is believed that the single role drones carry out is a caste in itself. This is strengthened by the close relationship between the words form and function (while ignoring sex), since drones have a different form and function than both worker bees and the queen. This opinion aligns with the belief that sex does not need to be taken into account when assigning caste divisions.

Alternatively, if there is only one role within one sex, then it can be argued that this one role is not separated into or defined as a caste. This argument aligns with the belief that sex does need to be taken into account when assigning caste division. Since the male honey bees only exist in one form and perform one function, there is no need to further define their existence past the basis of sex.

An important side note: Honey bees exist within their social hive network in ways that the human language cannot describe and human science endeavors cannot assign. We may never know the true breakdown of hive dynamics as honey bees see it! And besides, using words like “caste,” “form,” and “function” to describe honey bee societies is for the convenience of humans. Honey bees will (with our support!) perpetually carry out their role in the world, regardless.

Information was gathered for this blog via these sources:

https://americanbeejournal.com/ (February 2023 issue)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0sMv_gWaKLI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ePic3dtykk